EXPLORING THE DEFINITION OF “HUNTING” UNDER THE HUNTING ACT 2004

Introduction

1.There have been many issues with the idea as to whether “searching” for an unidentified or unidentifiable wild mammal could be classed as hunting under the Hunting Act 2004. It has also been a contentious issue regarding the actual meaning “hunting” under the Act. This issue was examined in the joint cases of DPP (Crown Prosecution Service CCU South West) v Anthony Wright; and the Queen on the Application of Maurice Scott, Peter Heard & Donald Summergill v Taunton Deane Magistrates Court [2009] EWHC 105 (Admin). The Court had made it clear that the interpretation of the Act in terms of the term “hunts” under the Act does not include the mere searching for an as yet unidentified wild mammal. Therefore, an illegal hunt will only begin, when a person or persons engage or participate in the pursuit of an “identified” wild mammal, they would then be guilty of an offence under the Act subject to the facts.

2. The Basic Offence

a) It is an offence under the Hunting Act 2004 to “hunt a wild mammal with a dog, unless his hunting is exempt”. The offence is subject to a statutory defence of reasonable belief that the hunting fell within an exemption and was therefore lawful – s 4

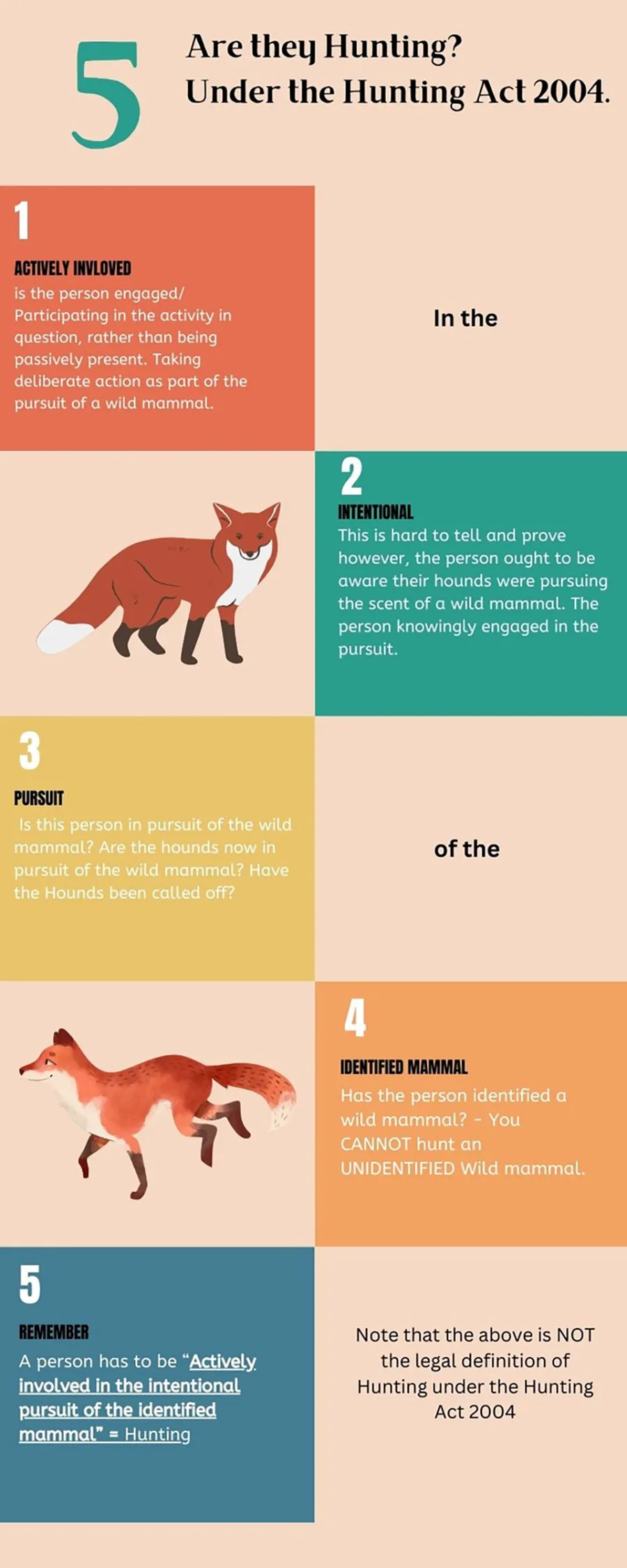

Actively involved in the intentional pursuit of the Identified mammal.

3. For the sake of clarity, the terms “engage” or “participate” mean that one must have an active and direct part in the hunting of the mammal; this is distinct from observing. As such only members of the field who “engage” or “participate” would be liable, not those merely riding regardless of their knowledge; one must be “Actively involved in the intentional pursuit of the Identified mammal”.

4. A suspect could argue that they were a follower and observer of the hunt and not actively engaging in the pursuit. The Hunting Act 2004 does not define “hunts” or “hunting” , although the interpretation under Section 11 does provide that a reference to a person hunting a wild mammal with a dogs does include any case where a person engages or participates in the pursuit of a wild mammal. Therefore, this suggests that hunting occurs when a person pursues an identified quarry. As such the prosecution will need to show that there is adequate evidence to prove the suspect engaged or participated in the pursuit. To be expressly clear, there is no offence of “attempting to hunt”, furthermore, hunting is, by definition, intentional. As offences under the Act are summary-only there can be no charge of attempt, unlike offences that are eitherway and indictable. This is found under the Criminal Attempts Act 1981.

5. In the round the difficulty with prosecuting a hunting offence case is the simple fact of whether or not the prosecution can in fact prove that the individual or individuals were “Actively involved in the intentional pursuit of the Identified mammal”. Essentially, a wild mammal which has never been identified as quarry has not suffered, which was the basis of the Legislation in the first place, to prevent unnecessary suffering to wild mammals. And yes, it’s easy for us to say that it’s obvious what is taking place when we see riders trotting across fields with hounds, but this view does not take into account the law and the subsequent judgements that have been decided. Although it’s important to note that the League would bring cases against hunt staff as opposed to its followers, one can assume this was due to the fact that a gentleman in a red jacket and terrier men on quads were easier to identify then the followers. Of cause many hunt sabs are aware of these individuals by name.

Are they “Hunting”?

6. The all-too-common issue that is faced when it comes to the legislation is whether or not the individual or individuals are in fact “hunting”? The League Against Cruel Sports encountered this issue when they first started to bring cases under the Hunting Act 2004. One of the main difficulties encountered was whilst it’s possible to gather great amounts of evidence of riders and hunt staff in what it looks like to be hunting, it was much harder to be able to obtain footage of people “actively” pursing an “identified” wild mammal as opposed to the mere searching of a wild mammal.

7. The phrase “hunts a wild mammal with a dog” in s 1 of the 2004 Act does not include the mere searching for an unidentified wild mammal for the purpose of stalking or flushing it out. A such a person to whom has left home intending to search for a wild mammal might be considered to be hunting but because he has not at that moment identified a mammal they would not be hunting.

8. Furthermore, although it’s easy to obtain footage of a fox bolting, seeking cover etc what is harder is to find footage of a member of the hunt actually being seen to be actively aware of this fact and participating in that material pursuit. However, that does not mean to say that there isn’t evidence out there. What is more common in fact is seeing and filming the hounds in cry often after pursuing a fox which has fled and the hunts master not calling his hounds off.

9. With reference to the above case law, it is important to take consideration of section 11(2) (a) & (b) of the Hunting Act 2004.

10. For the purposes of this Act a reference to a person hunting a wild mammal with a dog includes, in particular, and case where –

(a) a person engages or participates in the pursuit of a wild mammal, and

(b) one or more dogs are employed in that pursuit (whether or not by him and whether or not under his control or direction)

11. If we take the words “in particular” into isolation it allows for a somewhat broad interpretation of what “hunting” means in the context of an offence under the Act.

12. The Word “in particular” was argued by the League against cruel sports that there must be other elements to the offence as opposed to the ones outlined, this was because the word “in particular” gives rise to the argument that there must be other elements to the offence other than the ones mentioned above. However, it has to be said that this would make it hard to ever establish what elements were being taken into consideration when establishing what “hunting” could mean under the act and what elements were included within.

13. In the case of DPP v Wright the prosecution had contended that “hunting” includes searching for or hunting for a wild mammal as yet to be identified or is unidentifiable. The Judge did not accept this interpretation, they noted that there was a difference between “hunting a wild mammal” and “hunting for a wild mammal”. There is also a distinction between the phrases “hunting” and “hunting for” a fox.

14. With consideration to the facts of Mr Wrights prosecution, the opening words of paragraph 1(1) of Schedule 1 which state “Stalking a wild animal or flushing it out of cover” , it is clear to most that you cannot stalk an unidentified wild mammal by purely searching for it, nor would you flush out an unidentified wild mammal from cover, furthermore, the words “a wild mammal” and “it” require that the wild mammal has been identified, “Stalking a wild animal, or flushing it out of cover”

15. Taking a look at the conditions in paragraph 1 of the Schedule 1 of the Act are important, there are a set of 5 conditions. If all these conditions are satisfied, then a person can use the stalking and flushing out exemption contained in the Act. 16. For the benefit of the reader, we have put the full paragraph below:

1 (1) Stalking a wild mammal, or flushing it out of cover, is exempt hunting if the conditions in this paragraph are satisfied.

(2) The first condition is that the stalking or flushing out is undertaken for the purpose of—

(a) preventing or reducing serious damage which the wild mammal would otherwise cause—

(i) to livestock,

(ii) to game birds or wild birds (within the meaning of section 27 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (c. 69)),

(iii) to food for livestock,

(iv) to crops (including vegetables and fruit),

(v) to growing timber,

(vi) to fisheries,

(vii) to other property, or

(viii) to the biological diversity of an area (within the meaning of the United Nations Environmental Programme Convention on Biological Diversity of 1992),

(b) obtaining meat to be used for human or animal consumption, or

(c) participation in a field trial.

(3) In subparagraph (2)(c) “field trial” means a competition (other than a hare coursing event within the meaning of section 5) in which dogs—

(a)flush animals out of cover or retrieve animals that have been shot (or both), and

(b)are assessed as to their likely usefulness in connection with shooting.

(4) The second condition is that the stalking or flushing out takes place on land—

(a)which belongs to the person doing the stalking or flushing out, or

(b)which he has been given permission to use for the purpose by the occupier or, in the case of unoccupied land, by a person to whom it belongs.

(5) The third condition is that the stalking or flushing out does not involve the use of more than two dogs.

(6) The fourth condition is that the stalking or flushing out does not involve the use of a dog below ground otherwise than in accordance with paragraph 2 below.

(7) The fifth condition is that—

(a)reasonable steps are taken for the purpose of ensuring that as soon as possible after being found or flushed out the wild mammal is shot dead by a competent person, and

(b) in particular, each dog used in the stalking or flushing out is kept under sufficiently close control to ensure that it does not prevent or obstruct achievement of the objective in paragraph (a).

16. As mentioned above for the exemption in paragraph 1 to be used, all 5 conditions have to be satisfied. However, you would never reach the fifth condition unless you have actually identified the wild mammal and stalked it or flushed it out. Furthermore, a consideration which may lie in favour of the prosecutions view in relation to the Wright case, is the words “after being found or flushed out” in paragraph 1(7)(a). The court found that these words could not extend to determine the meaning of “hunts a wild mammal” in section 1 of the Act.

17. Honing on the 5th condition in relation to the Wright case, in which the fox had been seen on film moving quickly down a hillside, and each of the two hounds separately were seen to follow the same route after large gaps. Mr Wright stated that he had not appreciated the fox had been flushed out and never saw the fox at all. He said he sounded his horn to bring the hounds back and under control when he realised the hounds were pursuing a fox.

18. The court was not sure about the facts regarding this issue. The court was not sure whether the fox had been flushed from cover or was being “hunted”. Therefore, one can see the difficulty when establishing whether or not the person in scope is “hunting”

Conclusion

19. It is clear from the Judgment in the case of Wright that the terms “hunts” a wild mammal with a dog, as stated in section 1 of the Act, does not include mere searching for an unidentified wild Mammal for the purposes of stalking or flushing it. Hence it is clear that the term “hunting” does not include “searching” for an unidentified mammal As a result of the Wright case Defendants may claim that there is no evidence that their dogs were chasing a wild mammal or that they were unaware of this fact. Successful prosecutions against such a defence are based on proving that the mammal is specified, for example by footage that can identity the wild mammal, and as such the offence started with the earlier searching for it.

References

DPP (Crown Prosecution Service CCU South West) v Anthony Wright; and the Queen on the Application of Maurice Scott, Peter Heard & Donald Summergill v Taunton Deane Magistrates Court [2009] EWHC 105 (Admin)

Criminal Attempts Act 1981

S 11 (2) The Hunting Act 2004

Schedule 1 (1) of the Hunting Act 2004

The Hunting Act 2004 S1

The Hunting Act 2004

About the Author

James SF Hart provides legal analysis and commentary on issues related to fox hunting law and advocates for reform of the Hunting Act 2004.

Follow on social media